- Bone Health

- Immunology

- Hematology

- Respiratory

- Dermatology

- Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Rare Disease

- Rheumatology

Biosimilar mRNA Vaccines, Part 1: Regulatory Revolution!

Sarfaraz K. Niazi, PhD, discusses the regulatory approval of future messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, which will likely face fewer patent issues and are easy to replicate.

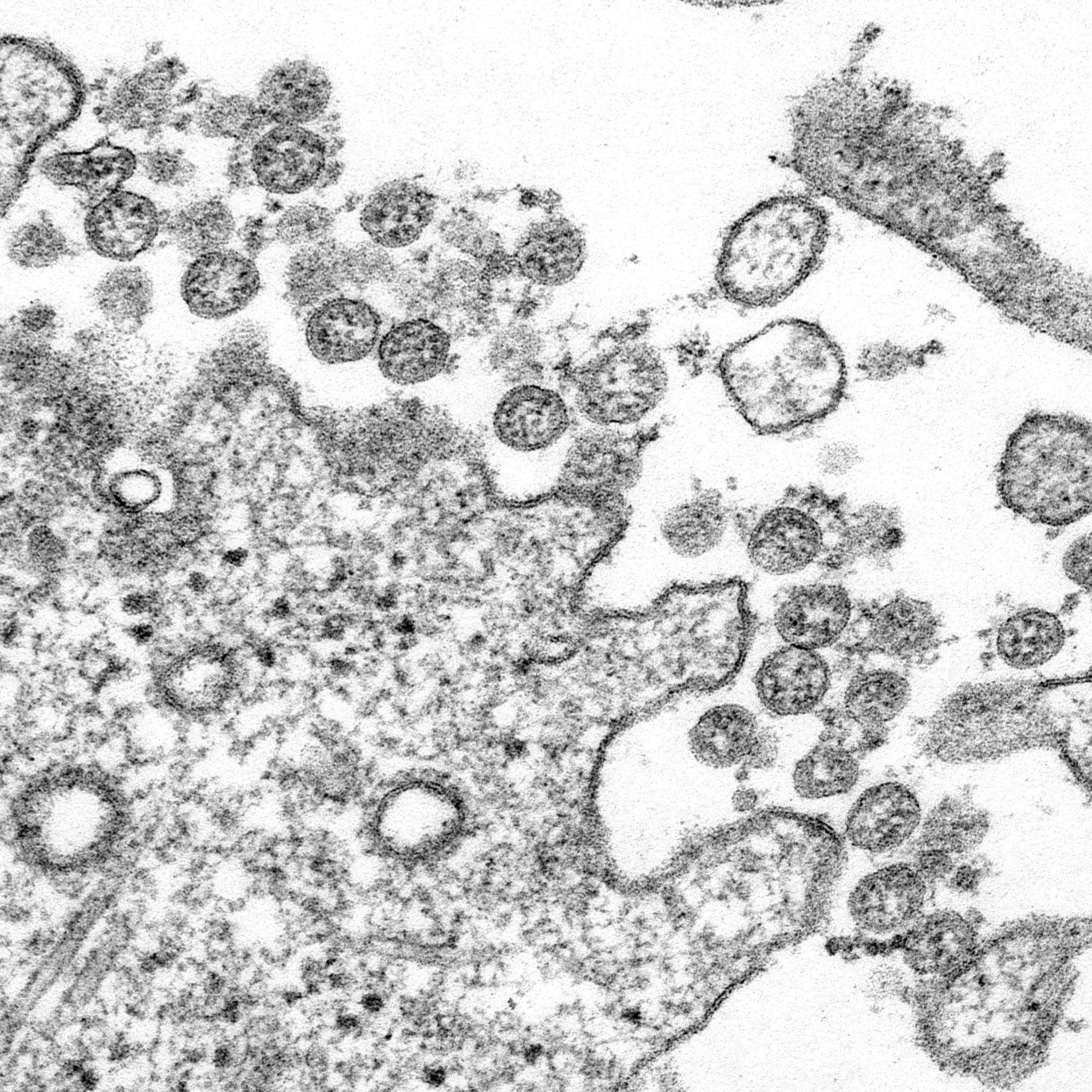

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a remarkable shift in how we will prevent infections and autoimmune disorders in the future. The nucleic acid vaccines, including messenger RNA (mRNA) and DNA vaccines, have been under development for decades, but there was no opportunity to test their safety and efficacy; vaccines may take years and decades to provide sufficient proof of safety and efficacy. Then came COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Fast data collection became possible because the virus was so widespread. Even with small infection numbers (n = 150) among study populations that averaged about 30,000 to 40,000, it was clear that mRNA vaccine efficacy was surprisingly high: 95% or better. The FDA would have approved the use of the mRNA vaccine at even at 50% efficacy.

The safety of the mRNA vaccines was confirmed clearly in multiple studies across the globe. However, not all COVID-19 vaccines fared well. The third mRNA vaccine, by CureVac, failed because its developers chose not to follow the teachings of the common wisdom. mRNA vaccines work by introducing a harmless piece of the virus into the body and triggering an immune response that conditions the body to recognize and attack the true virus. Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech vaccines use modified RNA (pseudouridine); CureVac chose not to modify the RNA, and its vaccine uses normal uridine. It produced lower levels of antibodies than the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines and was just 47% effective at preventing COVID-19 infection. Incidentally, the name Moderna comes from “modified RNA.”

The Chinese Sinopharm vaccine, a traditional inactivated virus vaccine, also failed. This failure brought great misery because the Chinese government had used this vaccine as a diplomacy tool, supplying billions of doses to developing countries. As of today, none of the non-mRNA COVID-19 vaccines have come close to the efficacy of the mRNA vaccines.

We have 2 mRNA vaccines approved under Emergency Use Authorization (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273/NAID), and I anticipate their full approval soon. Pfizer has filed for the modification of storage temperature, and Moderna has filed for the reduction of dose; the Pfizer dose is 30 mcg, and the Moderna dose, 100 mcg. There are now newer lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations that can provide better temperature stability allowing only refrigeration storage.

Incidentally, Moderna has permitted the use of its patented LNP technologies to any company. Although the challenges to overcome IP issues remain, the humanitarian considerations make these challenges manageable. The US government has proposed to remove patent exclusivity relating to the COVID-19 vaccines. This action will require EU cooperation that is yet to come. However, as a patent law practitioner, I am confident that we can make COVID-19 vaccines without any patent infringement that remains in our way. mRNA vaccines have been under development for decades, so much of the base technology is already in the public domain. Both Pfizer and Moderna have shared their clinical protocol, and that is a rare event, as these protocols cost millions to produce and billions to execute. No other vaccine developer has shared these protocols in public. The mRNA vaccine developers now have a clear understanding of the regulatory process required to approve new mRNA vaccines.

Regulatory Pathway

At the time of the enactment of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA, 2010), there was no indication that the introduction of mRNA vaccines would create a dilemma for the FDA in deciding an appropriate regulatory pathway.

The FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) jurisdiction includes biological products such as prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines, whole blood and blood products, cellular products and exosomal preparations, gene therapies, tissue products, and live biotherapeutic agents. CBER also regulates selected drugs and devices used to test and manufacture our biological products. In keeping with that mission, product approval applications filed with CBER include 351(a) filings, which are for “standalone” or original products, rather than biosimilars (21 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] 601.2). The biologics license application (BLA) is regulated under 21 CFR 600 – 680.

Many biological products are controlled by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), including biosimilar and interchangeable biologics. For example, in March 2020, insulin, glucagon, and human growth hormone regulated as drugs under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act came into the CDER BLA program.

mRNA vaccines have a unique feature: They are manufactured chemically, not biologically, as are many other vaccines. As a result, the vaccine structure is completely known, unlike the therapeutic proteins. The variations in the secondary and tertiary structures and post-expression modifications require intensive evaluation of similarity to allow them a biosimilar status. A proposed biosimilar mRNA vaccine can provide a 100% match for a reference product sequence. Thus, mRNA vaccines are closer to generic chemical products than biological therapeutic proteins.

In my opinion, the traditional vaccines can stay within the jurisdiction of CBER, and the chemically synthesized vaccines be approved under BLA by CDER under the 351(k) filing where suitable.

Already, the FDA has issued a final guideline (February 2021) on the development of products for the treatment and prevention of COVID-19, which states:

“COVID-19 vaccine development may be accelerated based on knowledge gained from similar products manufactured with the same well-characterized platform technology, to the extent legally and scientifically permissible. Similarly, with appropriate justification, some aspects of manufacture and control may be based on the vaccine platform, and in some instances, reduce the need for product-specific data. Therefore, FDA recommends that vaccine manufacturers engage in early communications with [Office of Vaccines Research and Review] to discuss the type and extent of chemistry, manufacturing, and control information needed for development and licensure of their COVID-19 vaccine.”

This statement can be construed as pointing to the possibility of a biosimilar application filing for a licensed (BLA) product to meet all requirements of the BPCIA. If the sequence of a biosimilar mRNA vaccine matches a reference product sequence, then the need for extensive toxicology and efficacy testing can be reduced, on a case-by-case basis, depending on other factors of variation. In my earlier conversation with the FDA, I appreciated the broad encouragement I received to discuss the development plan in a Type B meeting first, where the possibilities of a modified 351(a) filing or a 351(k) filing for a biosimilar mRNA vaccine can be discussed; the 351(a) modified approach will be analogous to a 505(b)(2) new drug application under the FDC Act. I will keep my readers informed of any new indications from the FDA.

mRNA vaccines are now at the forefront of hundreds of possibilities, including preventing infections to preventing autoimmune disorders. Since the antigens focused on the design of mRNA vaccines cannot be patented, a biosimilar vaccine product may likely produce the product without any infringement issue. The testing proposal presented above will help expedite the approval of biosimilars without risking the safety and efficacy of biosimilar products.

For the first time, we have a scientific challenge to meet: how to classify mRNA vaccines as chemical drugs or as biosimilars rather than standalone biologics?

Sarfaraz K. Niazi, PhD

To promote the idea of creating a new category of products, biosimilar vaccines, I have filed a citizen petition to the FDA advising the agency on creating new guidance for this new class of biosimilar products.

In contrast to chemically synthesized small molecular weight drugs, which have a well-defined structure and can be thoroughly characterized, biological products generally derived from living material (humans, animals, or microorganisms) are complex in structure and, thus, are usually not fully characterized. However, this last consideration does not apply to mRNA vaccines.

To promote the idea of creating a new category of products, biosimilar vaccines, I have filed a citizen petition to the FDA advising the agency on creating new guidance for this new class of biosimilar products. In my opinion, the agency will agree to many of my suggestions because the issue of structural similarity with a reference product is no longer an issue. Preclinical toxicology studies can be waived based on in vitro and situ studies, requiring only comparable antibody production in animal species. The immunogenicity—stimulation of immune response—is not a significant issue because vaccines are supposed to be antigenic. A limited trial in animal species capable of showing antibody response that is comparable to findings with the reference mRNA vaccine will suffice to establish equivalent safety with the reference product.

I have also developed several mRNA vaccines, including COVID-19, flu, HPV, HIV, and tuberculosis, that are under advanced stages of development across the globe, including one with a biosimilar status. Today, the world needs about 8 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines that work. I have concluded that we can make 1 billion doses using 30 L bioreactors in 6 months with our cost of goods not exceeding $0.50 per dose in bulk and $0.90 in final packaging if the vaccine is manufactured in the United States; the costs can be lower if manufactured in developing countries. For example, the cost of Moderna single dose is $32 to $37, and Pfizer’s, $22 in final packaging. I can confirm these costs of manufacturing that make the commercial manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines a highly profitable project.

While there is an excess of COVID-19 vaccine in the United States, the rest of the world is still starving for it. The WHO has also told me that the world needs 8 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines and that they will be very proactive if anyone can supply the mRNA vaccines; the trust in all other vaccines has declined. This is a remarkable business opportunity for many companies since the capital expenditures (CAPEX) and operating expenditures (OPEX) are very small. In my next article on the topic, I will provide details of strategies to take the mRNA vaccines to market fast and reduce CAPEX and OPEX significantly. I want to enable newcomers to appreciate that mRNA technology will revolutionize health care, and there are many opportunities to join this revolution.

Summary

mRNA vaccines are chemically derived and have fixed chemical structures; it is possible to fully replicate a reference product sequence, reducing the burden of proving biosimilarity required for therapeutic proteins. The FDA has already suggested a new pathway for mRNA vaccines, but this path will only come into being when enough companies join in taking steps toward this strategy.

Watch for the second article in this series: Biosimilar mRNA Vaccines—Fast-to-Market Strategies.

Newsletter

Where clinical, regulatory, and economic perspectives converge—sign up for Center for Biosimilars® emails to get expert insights on emerging treatment paradigms, biosimilar policy, and real-world outcomes that shape patient care.