In this dance, the biosimilar applicant takes the lead and ultimately dictates the scope of a first patent litigation. But, in the end, all hell can break loose.

- Bone Health

- Immunology

- Hematology

- Respiratory

- Dermatology

- Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Rare Disease

- Rheumatology

The Inner Workings of the BPCIA Patent Dance

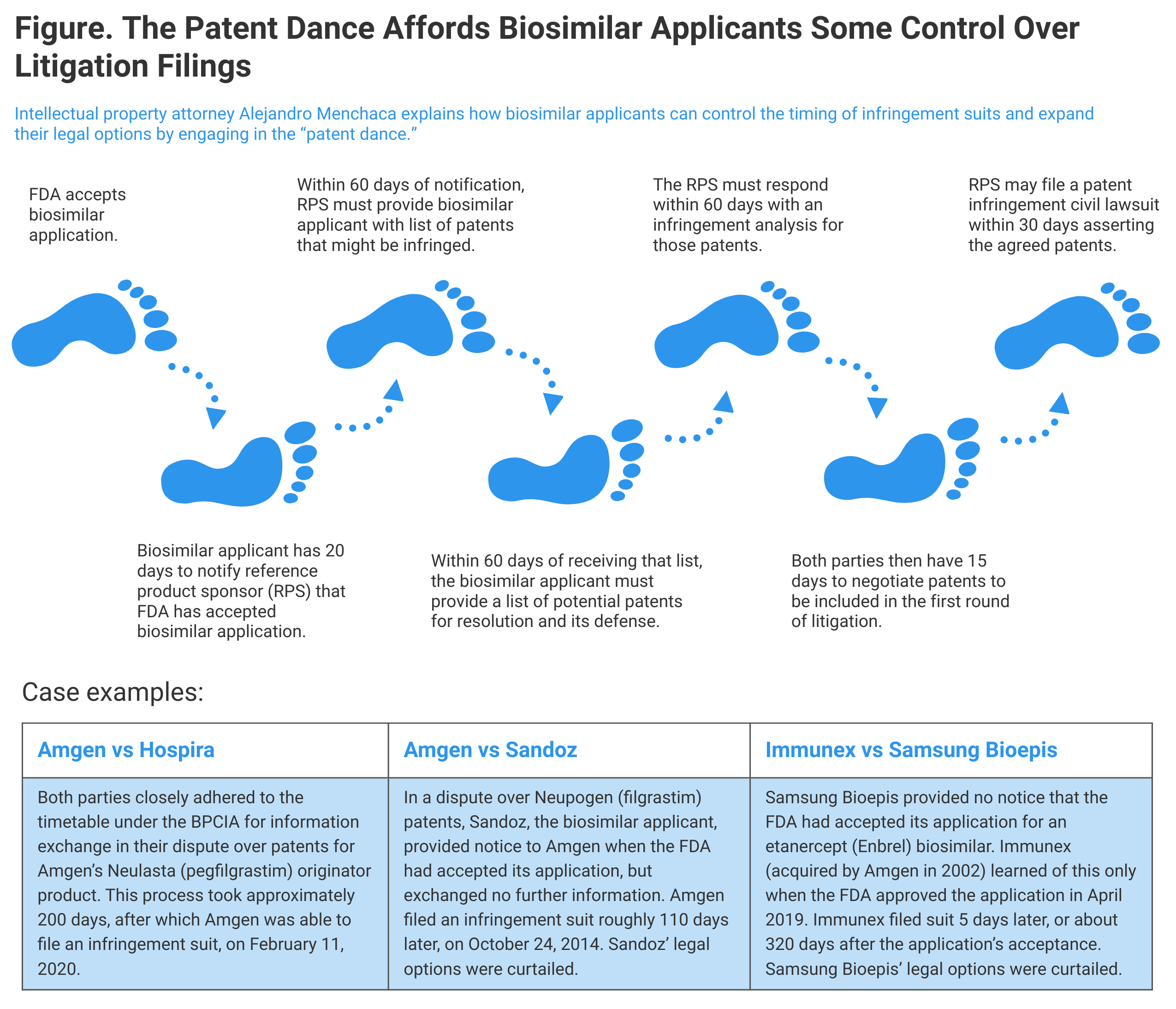

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) provides a stepwise approach for fact-finding prior to patent litigation, but companies may choose their own path, case examples show.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) created an abbreviated approval pathway for companies wishing to market biological products. In short, such companies may base their filing with the FDA on a previously-approved biological product. For approval under the abbreviated pathway, the biological product must be shown to be “biosimilar” to a previously-approved “reference product.”

The BPCIA also provides a framework for the biosimilar applicant and the reference product sponsor to address any patent infringement concerns raised by the biosimilar applicant’s marketing of the biosimilar (Figure). This framework provides the biosimilar applicant substantial control over when any patent infringement litigation will be filed. A review of a few examples of patent infringement complaints reveals different approaches taken by biosimilar applicants and shows how biosimilar applicants’ decisions on how closely to follow the BPCIA pathway may affect the timing of the ensuing patent litigation.

The BPCIA framework for addressing patent infringement concerns has often been called the “patent dance.” In this dance, the biosimilar applicant takes the lead and ultimately dictates the scope of a first patent litigation. But, in the end, all hell can break loose, as often happens in modern-day dancing, and the reference product sponsor can bring a second patent litigation with no further dancing under the BPCIA framework.

A Textbook Case

If the dance framework is followed to completion, a first patent litigation can be expected about 245 days after the FDA accepts the biosimilar applicant’s application for review. In one such case, Amgen v Hospira, the first patent litigation was filed 201 days after FDA acceptance. This case is a textbook example of how the dance framework timing can work. The BPCIA requires that the biosimilar applicant notify the reference product sponsor within 20 days of the FDA accepting the biosimilar application [42 USC § 262(l)(2)]. In Amgen v Hospira, this date was apparently August 15, 2019.

The 20-day notification triggers an obligation for the reference product sponsor to provide the biosimilar applicant with a list of patents that could be asserted against the applicant. That list must be provided within 60 days of receipt of the 20-day notification [42 USC § 262(l)(3)(A)]. In Amgen v Hospira, the reference product sponsor provided this list on October 14, 2019.

In response, within 60 days of receipt of the list, the biosimilar applicant provides its own list of potential patents for resolution and its defenses to the patents identified on the reference product sponsor’s list [42 USC § 262(l)(3)(B)]. In Amgen v Hospira, the biosimilar applicant, Hospira, could have waited until December 13, 2019, to provide its response, but did so on October 30, 2019—17 days after the patent listing—43 days sooner than necessary.

A further response by the reference product sponsor is required, again within 60 days. In this response, the reference product sponsor must set out its infringement analysis for those patents identified by the biosimilar applicant in its defense response [42 USC § 262(l)(3)(C)]. In Amgen v Hospira, the reference product sponsor, Amgen, took almost the full 60 days permitted and provided its response on December 27, 2019.

Click to enlarge.

The BPCIA framework then allots 15 days for the parties to negotiate which patents on the respective lists will be part of the first patent infringement litigation [42 USC. § 262(l)(4)]. In Amgen v Hospira, the parties completed their negotiation by January 13, 2020, and agreed that a single patent would be asserted in the first litigation. One would expect that Amgen identified in its patent list a whole host of other patents that could be asserted against Hospira, and that could have been part of the first litigation if the parties had agreed to include them in the first litigation. But, as noted, the parties agreed that the first litigation would include only 1 of the patents identified on the parties’ patent lists.

The BPCIA provides for an additional step if no agreement has been reached [42 USC § 262(l)(4)], but that was not necessary in Amgen v Hospira. Finally, the reference product sponsor, in order to preserve its right to damages other than a reasonable royalty [35 USC § 271(e)(6)(b)], may promptly (within 30 days) file a patent infringement civil action asserting the agreed patents [42 USC § 262(l)(6)].

In Amgen v Hospira, it appears that the FDA accepted Hospira’s biosimilar application on about July 26, 2019. Amgen sued on February 11, 2020. Assuming the July 26 date is accurate, the dance in Amgen v Hospira took 201 days.

Of course, the above BPCIA framework is not the end for Amgen and Hospira in that matter. As noted, the parties agreed to litigate only a single patent in the first litigation. But, there may be others—perhaps many—that Amgen may have available to assert in the second litigation. The second litigation triggers under 42 USC § 262(l)(8). Hospira must provide notice to Amgen of commercial marketing not later than 180 days before marketing [42 USC § 262(l)(8)(A)].

After that notice, Amgen may sue Hospira for patent infringement for all other patents that appeared on lists provided under 42 USC § 262(l)(3)(A) and (B). That’s where all hell can break loose, and, if those lists are extensive, the parties could be in litigation for quite some time on the previously-omitted patents. Because those patents available for the second litigation were already vetted by the parties in their exchanges under the BPCIA framework, no further information is required before the second litigation. Hospira’s biosimilar application was approved by the FDA on June 10, 2020. We can expect some action in this second phase of litigation in the near future.

Different Approaches

A completely different approach was taken by 2 other biosimilar applicants. In Amgen v Sandoz, the biosimilar applicant, Sandoz, chose to provide only the notice under 42 USC § 262(l)(3)(A). Sandoz engaged in no further dancing. In Immunex v Samsung Bioepis, the biosimilar applicant, Samsung Bioepis, skipped the dancing entirely. The reference product sponsor, Immunex, learned of the Samsung Bioepis biosimilar application only after the FDA published its approval of the Samsung Bioepis biosimilar.

The result of Sandoz’ actions under the BPCIA was that Sandoz lost control of the timing for when a lawsuit could be filed by Amgen and lost its right to file a suit for declaratory judgment

In Amgen v Sandoz, it appears that the FDA accepted Sandoz’ biosimilar application on July 7, 2014. Sandoz notified Amgen of that acceptance on July 25, 2014. Prior to that notification on July 8, 2014, Sandoz had advised Amgen that Sandoz expected FDA approval of its biosimilar in early 2015 and provided notice of commercial marketing pursuant to 42 USC § 262(l)(8). Subsequent correspondence from Sandoz to Amgen included offers to provide certain information about the biosimilar, but those offers were withdrawn.

Sandoz also repeatedly reminded Amgen that “Amgen is entitled to start a declaratory judgment action.” The result of Sandoz’ actions under the BPCIA was that Sandoz lost control of the timing for when a lawsuit could be filed by Amgen and lost its right to file a suit for declaratory judgment [42 USC § 262(l)(9)]. The practical result was that Amgen tired of Sandoz’ shenanigans and filed its suit for patent infringement on October 24, 2014—about 110 days after the FDA accepted Sandoz’ application. No doubt Amgen was motivated to file the lawsuit before Sandoz’ commercialization, but Amgen could have waited until any later time to file the lawsuit.

In Immunex v Samsung Bioepis, the reference product sponsor first learned of the biosimilar applicant’s (Samsung Bioepis) application on April 25, 2019 when the FDA published its approval of the biosimilar. Immunex sued Samsung Bioepis on April 30, 2019, alleging that Samsung Bioepis “failed to provide to Immunex any of the information specified by 42 USC § 262(l)(2).” From a review of other cases, it appears that in 2019 the FDA approved a biosimilar application about 320 days after the date of acceptance. Assuming a similar time frame for the Samsung Bioepis application, it may be that Samsung Bioepis’ approach resulted in litigation in about 320 days. As in Sandoz, here the biosimilar developer lost the ability to file a civil action for a declaratory judgement as a result of its failure to follow the BPCIA framework.

The above examples provide some insight into how the biosimilar applicant’s decisions on whether to follow the BPCIA framework may affect the timing of the ensuing patent litigation. Although adhering to the BPCIA framework provides some clarity to the process, for example, an early identification of the patents at the reference product sponsor’s disposal to assert, other consideration may counsel using only part of the BPCIA framework or none at all. Also, given that patents identified in the parties’ 42 USC § 262(l)(3)(A) and (B) lists are now identified in the Purple Book, subsequent biosimilar applicants can use that additional information in preparing their strategies for how to proceed under the BPCIA.

The opinions expressed here are the present opinions of the author and may not reflect the opinions of McAndrews, Held & Malloy, its clients, or any individual attorney or employee. This is for general information purposes and is not intended to be, and should not be taken as, legal advice.

Newsletter

Where clinical, regulatory, and economic perspectives converge—sign up for Center for Biosimilars® emails to get expert insights on emerging treatment paradigms, biosimilar policy, and real-world outcomes that shape patient care.